Advertising is becoming more pervasive and advergames, games for promotional purposes, play an ever increasing role. This blog post will underline the narrative components of a very successful case in this field, Magnum Pleasure Hunt (MPH), and its relation with other traditional advertisements for the same brand.

Magnum Pleasure Hunt (Lowe Brindfors, 2011) was part of a worldwide online campaign launched by Unilever to promote its Magnum ice-cream products. In terms of reach, the game was considered highly successful – with more that 7.000.000 players and an average engagement of 5 minutes for each user. The campaign propagated virally on several social networking sites and its hashtag was one of the Twitter trends the day of its launch. In this sense, MPH was deemed a success and convinced Unilever to finance two sequels in the following years.

From a more ludological point of view, MPH can be critiqued for its game-design shortcomings, for example flaws in level design. However, this specific post will concentrate on the narrative and semiotic features that MPH shares with other commercials.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LVEnHsnNxmg

MPH is a Flash-based side-scrolling platform game, following most of the conventions of this genre. Its main narrative theme is “a Hunt for Pleasure across the Internet”, represented by the avatar trying to collect the highest possible number of Magnum products while literally running through several commercial websites – both fictional and depicting real-world brands. The designers of MPH transformed ordinary webpages into rudimentary game levels: while eidetic, chromatic and figurative components of webpages (abstract forms, colors and represented images) remain the same, their functions are altered – i.e. a text box is no more simply part of a page but also becomes a platform over which the avatar can jump.

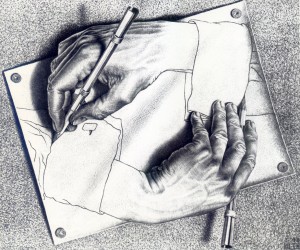

While the dream of French Structuralism of developing a universal, canonical narrative schema is no longer plausible, this school of thought still provides useful tools for analyzing specific commercials. Parts of their methodology can help us understand advergames and serves as a complement to other descriptive methodologies in this field.

From a semiotic perspective, advertising relies on simple plans that isolate the core values of a brand and actualize them in a compelling narrative text exemplifying their identity, their essence.

Some well-know semiotic mechanisms govern this strategies, such as embodying core values in actors and objects and composing a basic narration – often a simplified “quest narrative”. In the past decade, Unilever associated its Magnum brand with luxury and pleasure, inventing and marketing the Magnum bliss as a euphoric, temporary state reached through chocolate-covered ice-creams. Its core values, luxury and pleasure, are complementary in recent Magnum texts: sometimes one is presented as instrumental for reaching the other, but the Magnum brand identity incorporates both. The MPH advergame also adheres to this strategy.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0mVK5QcP1Vs

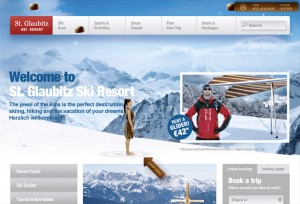

Pleasure, luxury and their related semantic associations are translated quite literally into MPH, in its levels and in some game-elements. As the title suggests, MPH represents the avatar’s hunt for the highest possible form of pleasure as she runs across several websites suggesting pleasurable situations. During gameplay, the avatar traverses a good number of upscale websites (and the player, metaphorically, browses them) from hi-tech gadgets to haute-couture, exotic hotels and spas. Cutscenes between levels show other luxury experiences – a shower in an expensive hotel, renting a glider on the Swiss Alps – but the protagonist sprints past all of them. During her quest for “ultimate pleasure”, the avatar encounters two varieties of Magnum icecreams: first, “Magnum bon-bons” must be collected to earn points and, later, a full-size Magnum Caramel icecream is presented as the final reward – the object embodying ultimate pleasure and luxury. From a structural semiotic point of view, the main subject is on a quest and tests several potential objects before finding the perfect one, the Magnum icecream, that emerges as the best synthesis of pleasure and luxury.

However, in conclusion, we have to remember that – even if it was considered a success as a viral campaign that propagated across social media – MPH is not a satisfying game per se for a number of reasons outside the scope of this post. In brief, what we can say here is that despite an unusually high production value, the designers of MPH reduced agency to safeguard narrative development and consistency. For example, it is impossible to lose/fail as the avatar always reaches the end of the game: in this way the quest always ends by reaching the Magnum-branded apotheosis. This is obviously atypical and disappointing from a ludic perspective.

We have described how narrative structures and narrative roles are used in advertising and advergames to express the core semantic values characterizing a brand-identity. MPH has been successful in engaging a considerable number of players and represents a good example of how commercials are currently being translated into advergames. Magnum Pleasure Hunt demonstrated, once again, to advertisers and creative directors the potential and the reach of advergames – we hope that, in the future, such products will feature ludic elements as polished as their production value.

More reading